A Rant about Loops and Bypasses

- Robin Cole-Jett

- Dec 31, 2024

- 6 min read

I am an urban planning nerd. While I have no formal training, I'm here to rant that loop highways and bypasses are stupid ideas, and nowhere is their misuse more evident than in the Red River Valley.

Cities use loops and bypasses to funnel traffic away from their downtown cores. City councils and state highway departments decided that, as 18-wheelers became more numerous and larger, the narrower streets in the older parts of town were not necessarily ready or able to handle through-traffic, and loops and bypasses designed for speed allowed convenient connections to state and federal highways. That makes sense, right? Well, it was a short-sighted plan. Cities throughout the region initiated these loops and bypasses to the point of their own destruction.

The problem centers on an obvious side effect --it wasn't only commercial vehicles being routed. The traveling public also uses the convenient highways, where they can travel faster. This siphons off non-local traffic that would normally take advantage of shops, stores, and restaurants in the town's centers. It's the whole point of paved roads that snake through towns: they are literally designed for town-to-town touring.

A History of Streets!

The Good Roads Movement, which began in the 1880s as a push to build usable bicycle paths, became a national concern that encouraged automobile touring to increase tourist and commercial traffic (as well as military maneuvers). "Good Road Committees" that encouraged regional connections were a response to the Great War, during which shipping and travel witnessed troubles with the privately-owned railroads. To circumvent threats of strikes, funding issues, ticket scalping, and labor shortages, the focus of national traffic turned to publicly-funded roads that could deliver goods as well as people. By the 1930s, motels (motor hotels) and cheesy tourist attractions competed for the traveling public's dime. The WPA even released touring books in the 1940s to further encourage automobile tourism that could add to the coffers of towns reeling from the Great Depression. During the latter half of the 20th century, the "great American road trip" was almost a rite of passage. Local historical and preservation groups used tourist dollars (some in the form of hotel occupancy taxes) to open museums and parks to further encourage road-use consumption and take a portion of American's disposable incomes.

Throughout the Red River Valley, federal and state highways were built to bring economic growth to communities along the paths. Here are some examples:

US 71, the first paving project in western Arkansas, originally followed an Indian path that connected the Caddo homelands to the Hot Springs. A usable thoroughfare increased tourism and developed the bathhouses in scenic Hot Springs, Arkansas.

The Bankhead Highway (US 67 through Arkansas and Northeast Texas, then US 80 past Dallas), an eponymous route championed by an Alabama Senator, connected Washington DC to San Diego, California. Its popularity created a network of other roads such as US Highway 82 (through North Texas) and 70 (through Oklahoma), which were both interchangeably known as the Bankhead and Southern National Highways, and US 80, aka the Dixie-Overland Highway through northern Louisiana and into eastern Texas.

The Jefferson Highway (US 69 for the most part) was touted as the "Pine to Palm" highway, as it reached from Canada to New Orleans; the King of Trails (US 75) connected the Midwest to the Gulf of Mexico; and the Meridian Highway (US 81) was promoted for paralleling the "Chisholm Trail." The tourist-aspect of these roads is very obvious!

There are several more examples, but the most well-known one is the Ozark Trail, aka Route 66. Its original alignment brought tourism into western Oklahoma (such as Anadarko and Greer County) and the Texas panhandle (Childress). Its straightened path that connected Oklahoma City to Amarillo and further westward into New Mexico, Arizona, and California has become the quintessential tourist attraction for US Americans and international tourists alike.

Loop de Loop

Loop highways emerged as urban planning trends in the mid-20th century in larger cities like Dallas to ease congestion. Belt Line Road, originally designed as part of the Kessler Plan in 1911 to remove railroad traffic from downtown Dallas, became a 90-mile automotive highway loop instead. As the city kept growing, the construction of further loops (Loop 12 and Interstate 635) that connected to federal highways, many of which were straightened to become interstate highways in the 1950s and 1960s, changed the function of downtown. Due to these convenient roads, travelers could circumvent the central business district, and they did. Think about it -- how many people (besides me!) actually drive through Dallas not via Interstate 35E but on Harry Hines and Jefferson Boulevards?

The loops and bypasses also fed suburbanization. Locals desired faster options to get to work, and neighborhoods of tract houses designed specifically for commuting allowed them to live next to highways instead of stores and other necessity businesses. The commercial landscape no longer relied on urban density in beautiful but human-sized downtown cores, but on low-slung strip malls with acres of parking lots to accommodate convenience. Downtown Dallas then reinvented itself as a mini-New York, with prohibitive skyscrapers replacing entire city blocks. The city lost its public spaces.

Population is Key

But the large cities, like Dallas and Fort Worth, can kinda-sorta absorb the social costs that loop highways bring. They have the population densities that can afford these changes, especially now with the downtown revivals of major cities throughout the United States. The loops have become de-facto economic barriers, even: real estate prices are substantially higher in Dallas for properties inside Loop 12 on the north side of town, and I-30 differentiates between "the haves" and "the have-nots."

This isn't the case for mid-sized and small cities in the Red River Valley, though. Loops and bypasses have significantly hindered economic progress in the city centers.

The signs for Loop 220 practically entice travelers to bypass downtown Shreveport. Loop 369/151 in Texarkana and the "flying highways" that have cut through the heart of Wichita Falls also discourage travelers from entering downtown. These downtowns can ill-afford the siphoning of business away from their cores, as evidenced by dilapidation along Texas Avenue in Shreveport, blocks of empty lots in the center of Texarkana, and the sad state of Scott Avenue through Wichita Falls.

The smaller cities fare even worse. When developers built shopping centers along Paris's Loop 288 in Lamar County, Texas, the downtown, which had been the center of commerce with department stores like Sears, Belk's, and JC Penney, witnessed abandonment. In Seymour (Baylor County, Texas), the US 183/283/82/277 bypass has an unofficial nickname - "See Less of Seymour." And don't get me started on Sherman/Denison in Grayson County, Texas... Texoma Parkway has become a shadow of its former glory thanks to the US 75 bypass.

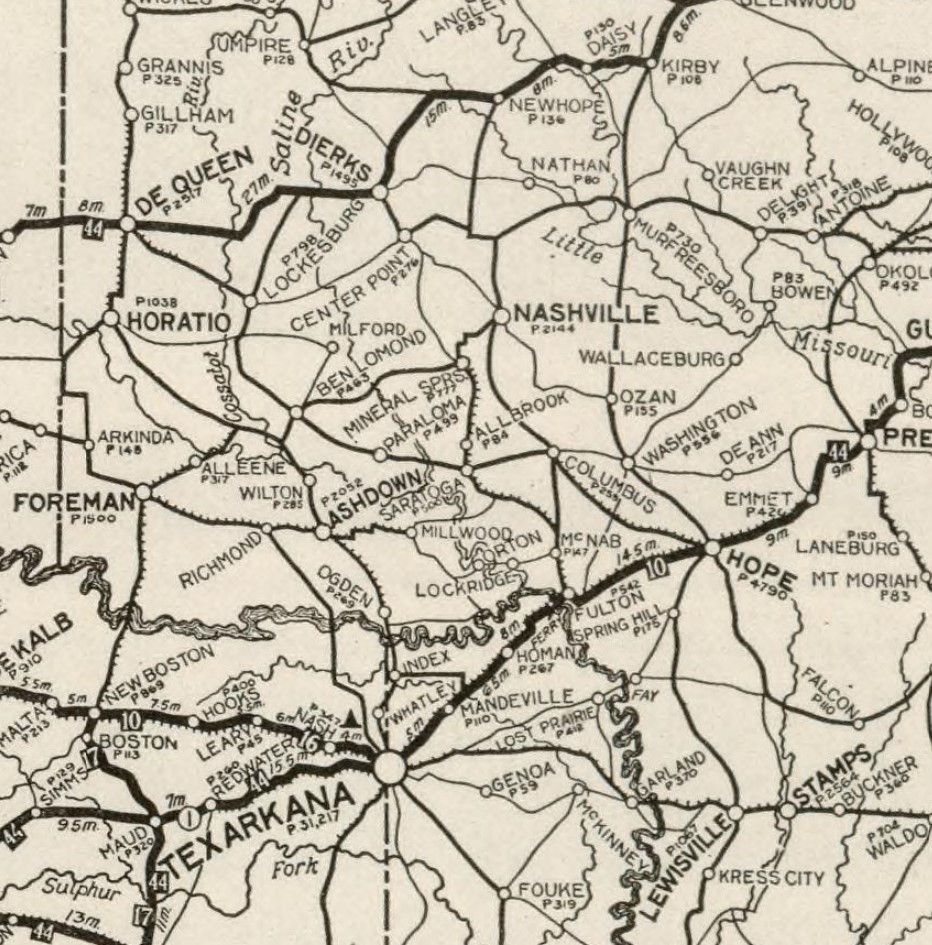

The worst to be hit from bypasses, though, are the towns that are not county or parish seats. Fulton (Hempstead County, Arkansas) and Garland (Miller County, Arkansas) were once through-fare traveling destinations, but are now completely bypassed - you'll have to WANT to go to these towns to be in these towns.

Downtown Revivals

Traffic generated by locals cannot replace the need for the additional business that through-traveling brings to economies. Luckily, the traveling public often recognizes this and makes it a point to traverse the original thoroughfares. Downtowns are now enjoying revivals, like certain areas of Wichita Falls (coffee shops and breweries) and Clarksville (Red River County, Texas), where business has picked along Main Street after the US 82 bypass was built. Much of this has to do with the increase in population brought on by regional economic development and long-range planning in recent years.

The good news comes on the affordability front. Houses can be extremely affordable in places like Electra (Wichita County, Texas) and Vivian (Caddo Parish, Louisiana) if you don't mind contributing some elbow grease. Wichita Falls, Shreveport, and Texarkana are ripe for urban pioneers to reshape old town landscapes. Of course, gentrification has a definitive downside, because locals might find themselves priced out of their own hometowns.

And this is why the United States is constantly on the move.

Comentários